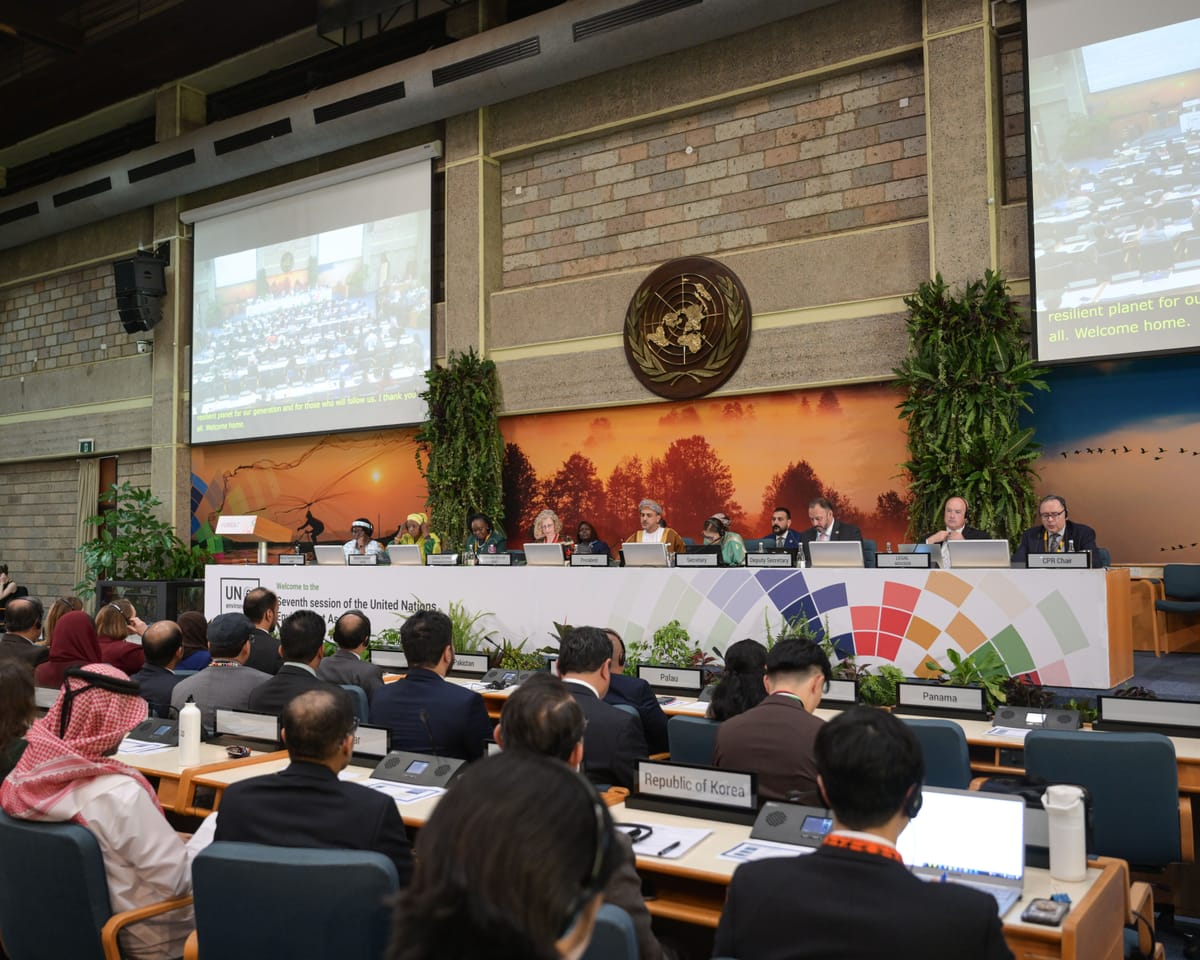

It is appropriate that this week’s United Nations environmental discussions are happening in Nairobi, as Africa plays a central role in shaping global climate dialogue. Diplomats from the continent are addressing the complex issue of whether attempting to cool Earth by reducing sunlight exposure is a prudent approach. While not officially on the summit agenda, African representatives are urging an end to framing solar geoengineering as a viable response to planetary warming — a stance difficult to contest.

African governments have mobilized against becoming testing grounds for speculative projects aiming to inject atmospheric particles to deflect solar radiation for minimal, uncertain cooling benefits. They emphasize environmental, ethical, and geopolitical dangers, advocating instead for an international agreement prohibiting public financing, outdoor trials, patent claims, and government endorsement of these technologies.

The rationale for restraint is clear: solar geoengineering fails to reduce greenhouse emissions. Potential consequences include disrupted rainfall patterns threatening food security and the peril of sudden temperature surges if interventions cease — known as termination shock. Last year, African opposition compelled the withdrawal of a Swiss-proposed resolution on solar radiation modification during UN negotiations.

Nonetheless, an industry is emerging around controlling Earth’s climate systems. A U.S.-Israeli company is designing spray systems for future governmental "cooling services," while pushback grows. Mexico banned solar geoengineering tests in 2023 after a U.S. startup conducted unauthorized experiments.

Academic critics note that the U.K.’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency recently became the first major government to fund solar radiation modification (SRM) research, backing hardware development and small-scale trials. Scientists have labeled this poorly governed and ineffective at proving SRM’s safety, urging policymakers to reconsider.

Research initiatives carry political dimensions. Infrastructure and careers depend on them; risky technologies attract deep-pocketed supporters. The role of the United States — the top oil and gas producer — warrants scrutiny. Solar geoengineering could allow temperature management without loosening fossil fuel dependence, aligning with interests seeking simultaneous control over energy systems and climate mechanisms.

Africa’s proposal for a solar geoengineering non-use pact — mirroring bans on landmines and chemical weapons — acknowledges that some technologies concentrate power so radically they create uncontrollable threats. A boundary must be established.

Read next

Might Narcolepsy Medication Revolutionize the World?

Breakthroughs in Sleep Science Reveal Surprising Insights

During a conversation with a pharmaceutical researcher, I learned of significant progress in sleep medications. One promising development targets narcolepsy, though its method could also address broader sleep issues like insomnia, much like how certain unexpected innovations find wider applications — akin to adhesive

"Far right still dominant in Netherlands despite Wilders' government setback"

Dutch Voters Head to the Polls Amid Political Instability

On Wednesday, Dutch citizens will cast their votes once again, marking the ninth election for the Tweede Kamer—the legislative chamber of the Netherlands’ parliament—in this still young century. In some respects, the country has come to resemble Italy in

"Spirituality is a fluid, evolving practice that brings clarity to life's mysteries, not rigid doctrine."

As I prepared to leave London for Melbourne, my eldest sister-in-law reminded her children to honor the “tradition”—tossing a bowl of water behind me as I walked out the door. Just a light spill on the ground, a custom far older than nations. *"La har azaab po aman