A friend recently shared two major achievements: his first book had been published, and he had been granted tenure at his university. Yet, he confessed, he felt miserable. How could he celebrate his success while so much suffering unfolded elsewhere?

This is a question many are asking. At this moment, severe crises grip Gaza, Sudan, Yemen, Myanmar, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Efforts to address climate change have lagged, pushing the planet closer to becoming inhospitable. Meanwhile, in the United States, immigrants have been detained and deported without due process. Transgender individuals face increasing hostility. Essential institutions have been weakened, research undermined, universities challenged, and the legal system strained by corruption.

Is it wrong to find happiness amid such devastation? Or is it unwise to anchor one’s well-being to a world so unpredictable and often unjust? I told my friend that both perspectives hold truth: if he allows himself to feel the world's sorrow, he should also embrace its moments of joy. This reflects an ancient principle worth remembering.

Many cultures and faiths emphasize shared human suffering. A common metaphor portrays humanity as parts of a single body. Variations of this idea appear in Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic, Jewish, and Christian teachings.

For instance, St. Paul wrote in a letter to the Corinthians: *“For just as the body is one and has many members…so it is with Christ…If one member suffers, all suffer together.”* Centuries later, Ralph Waldo Emerson offered a secular take: *“It is a doctrine alike of the oldest and of the newest philosophy, that man is one, and that you cannot injure any member without a sympathetic injury to all.”*

Those questioning their right to happiness today align with this noble tradition. It is both rational and ethical to feel distress when others are harmed.

Yet shared feeling should not be limited to pain. The same passage from St. Paul continues: “If one member is honored, all rejoice together.” The logic holds—if we sorrow with others, should we not also celebrate their triumphs?

Some Buddhist teachings consider this part of enlightenment. Practitioners are encouraged to extend their awareness universally, embracing the happiness of others. This concept, called *mudita*, is often translated as sympathetic joy. The German term *freudenfreude*—delight in another’s good fortune—encapsulates the idea well.

When we hesitate to welcome happiness, we risk rejecting a universal principle: joy, like sorrow, binds us together.

Read next

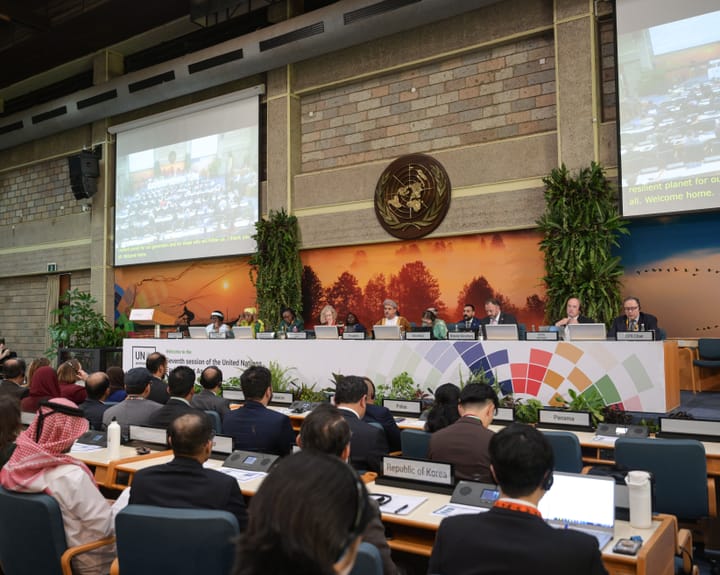

Africa's Warning on Solar Geoengineering Risks Gains Editorial Backing

It is appropriate that this week’s United Nations environmental discussions are happening in Nairobi, as Africa plays a central role in shaping global climate dialogue. Diplomats from the continent are addressing the complex issue of whether attempting to cool Earth by reducing sunlight exposure is a prudent approach. While

Might Narcolepsy Medication Revolutionize the World?

Breakthroughs in Sleep Science Reveal Surprising Insights

During a conversation with a pharmaceutical researcher, I learned of significant progress in sleep medications. One promising development targets narcolepsy, though its method could also address broader sleep issues like insomnia, much like how certain unexpected innovations find wider applications — akin to adhesive

"Far right still dominant in Netherlands despite Wilders' government setback"

Dutch Voters Head to the Polls Amid Political Instability

On Wednesday, Dutch citizens will cast their votes once again, marking the ninth election for the Tweede Kamer—the legislative chamber of the Netherlands’ parliament—in this still young century. In some respects, the country has come to resemble Italy in