Do People from Different Backgrounds Perceive the World Differently?

Two recent studies have revisited the long-standing debate over whether people from varying cultures and environments perceive the world in distinct ways. The findings suggest that the answer may be more nuanced than either study alone proposes.

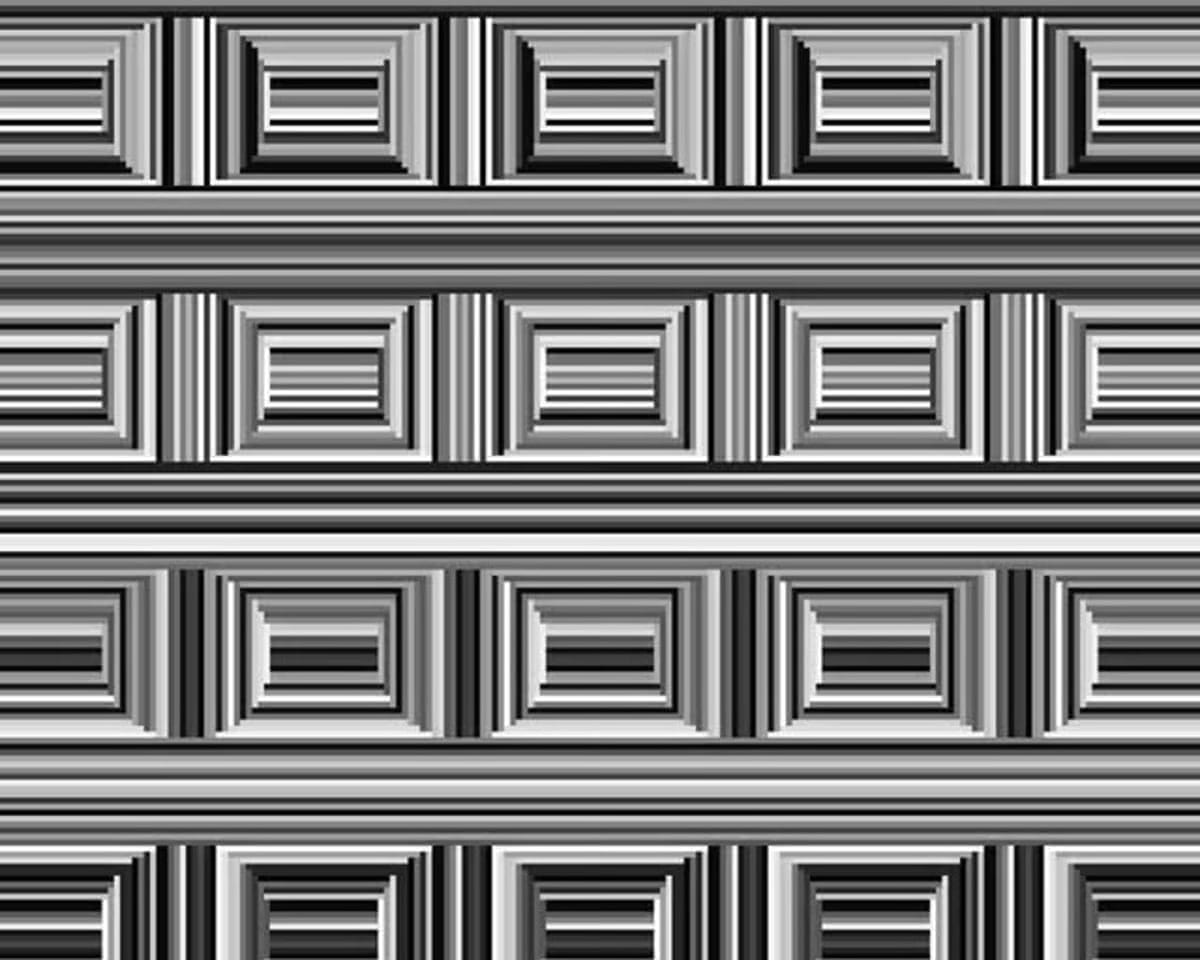

One investigation, conducted by Ivan Kroupin at the London School of Economics, explored how individuals from different cultures perceive the Coffer illusion. Their results indicated that participants from the UK and the US primarily saw the image as composed of rectangles, while those from rural Namibia tended to perceive it as containing circles.

To explain these differences, Kroupin’s team referenced a hypothesis first proposed over 60 years ago. The theory suggests that people from industrialized Western countries—often categorized under the acronym “WEIRD” (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic)—process visual information differently due to frequent exposure to structured environments with straight lines and right angles, common in urban architecture. In contrast, those from non-industrialized societies, like rural Namibia, live in surroundings with fewer rigid geometric forms, leading to alternative visual interpretations.

The study argues that Namibians’ tendency to see circles in the Coffer illusion reflects their exposure to curved structures, such as round huts, rather than angular ones. Additional studies on visual illusions support this interpretation, suggesting that basic perceptual mechanisms vary with environmental influences.

However, a second study by Dorsa Amir and Chaz Firestone challenges this hypothesis using the Müller-Lyer illusion, a well-known visual effect where two lines of equal length appear different due to arrowhead markings. This illusion has often been attributed to the brain interpreting the lines in three-dimensional space, aligning with the “carpentered world” hypothesis. Past research even cited cultural differences in perception as evidence.

Amir and Firestone rigorously refute this explanation. They highlight that non-human animals also experience the illusion, as demonstrated in multiple experiments involving species such as pigeons and primates—creatures not raised in human-engineered environments. Their work suggests that the illusion may arise from more fundamental neural processes rather than cultural conditioning.

These contrasting findings underscore the complexity of perception, revealing that both environmental influences and inherent cognitive mechanisms shape how individuals interpret visual information. The debate remains open, indicating that human perception is far from fully understood.

Read next

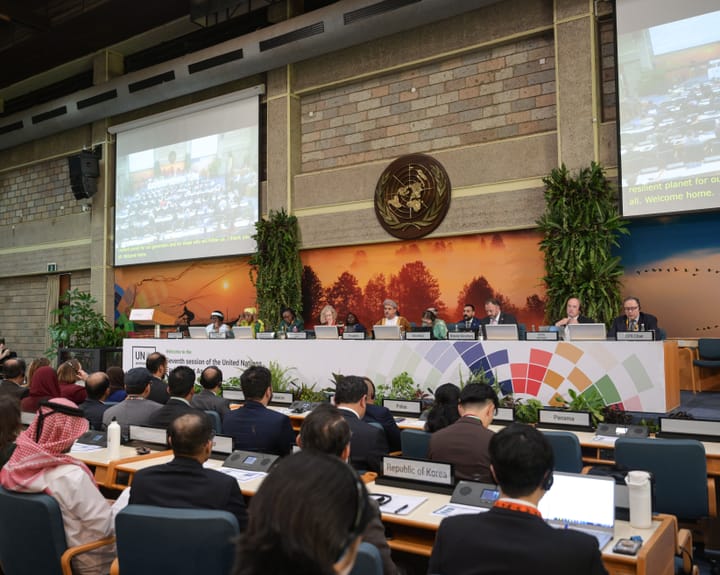

Africa's Warning on Solar Geoengineering Risks Gains Editorial Backing

It is appropriate that this week’s United Nations environmental discussions are happening in Nairobi, as Africa plays a central role in shaping global climate dialogue. Diplomats from the continent are addressing the complex issue of whether attempting to cool Earth by reducing sunlight exposure is a prudent approach. While

Might Narcolepsy Medication Revolutionize the World?

Breakthroughs in Sleep Science Reveal Surprising Insights

During a conversation with a pharmaceutical researcher, I learned of significant progress in sleep medications. One promising development targets narcolepsy, though its method could also address broader sleep issues like insomnia, much like how certain unexpected innovations find wider applications — akin to adhesive

"Far right still dominant in Netherlands despite Wilders' government setback"

Dutch Voters Head to the Polls Amid Political Instability

On Wednesday, Dutch citizens will cast their votes once again, marking the ninth election for the Tweede Kamer—the legislative chamber of the Netherlands’ parliament—in this still young century. In some respects, the country has come to resemble Italy in