Families of 20 men who declined military service in defense of former Dutch territories now seek official recognition that their ancestors stood firmly against warfare for Indonesian independence from colonial rule, rather than being labeled as deserters or cowards according to historical records.

An investigation into the era following World War II's end uncovered severe violence by a failed military offensive in efforts to maintain Dutch control over colonies that had claimed their freedom on August 17, with numerous innocent villagers falling victim—an act resulting ultimately in compensation for affected families.

Former Prime Minister Mark Rutte issued an apology in recent years (2022), and his administration consented to reevaluating the records of those who objected on moral grounds if they were aware of this rampant violence, potentially restoring their honorable titles within history's pages.

Now descendants from a group known as Indonesië-weigeraars are urging current officials for rectification concerning how ancestors named Jan de Wit suffered imprisonment alongside WWII adversaries—a period when conscription was directed against individuals who resisted military involvement to suppress the newly independent Republic of Indonesia.

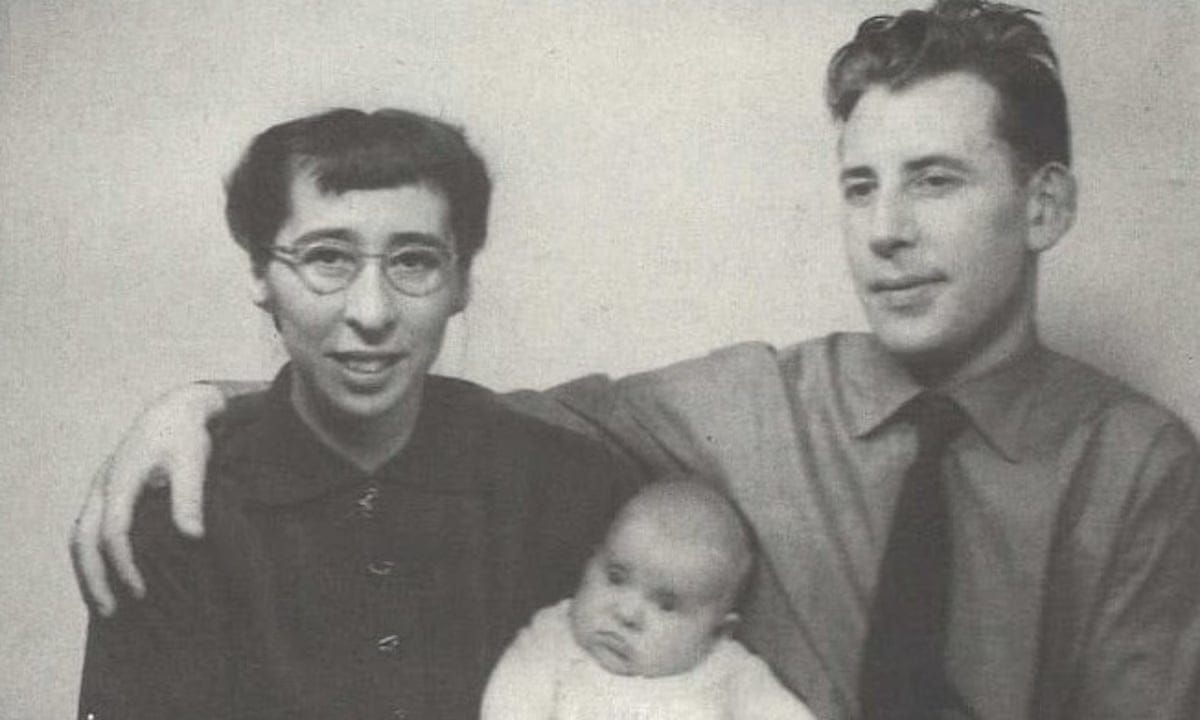

"My father originated from a communist perspective and held deep respect towards independence calls for our nation," said Nel Bak, age 68 hailing from Middenbeemster; she pleads with her mother at over ninety years old that their family should be pardoned as records wrongly mark him.

The Dutch government in the past mandated enlistment of around half a million men to combat Indonesian independence, which was declared on August 17—a move driven by an unwillingness not just for territorial loss but also due to relinquishing economic interests despite being overtaken after Japan's defeat. The struggle adopted increasingly violent tactics as the Dutch forces were outmatched and sought guidance from their government, leading local citizens into turmoil with frequent extreme violence against them by armed troops in close cooperation—a fact later disclosed through official investigations.

Eelco van der Waals's experience echoes these sentiments: he received an apology for his father Koos’ imprisonment as a pacifist, but full rehabilitation is what brings the truth to light and educates future generations—not just acknowledgment of past mistakes. His grandfather resisted orders that required lethal action in training scenarios because such acts clashed with deeply held convictions on life's sanctity; hence his place among history must be recognized for these reasons alone, without apologies overshadowing it completely.

Peter Hartog also champions the cause of complete rehabilitation—not just restoration to reputation but an erasure that removes entire sentences and castigating histories from records: "My ancestor stood up against his choices in times when he had no option, deserving a chapter written with respect for nonviolence," proclaims the seventy-year old.

Jurjen Pen—a legal advocate on behalf of those who refused to fight—criticizes the unfair burden placed upon relatives having only limited knowledge due in part to communication barriers and decades long downplaying by authorities; he calls for a full pardon under Dutch law as an act that says "the Netherlands was wrong, not just on face value but fundamentally."

Yet Klaas Meijer of the Ministry of Defense counters these demands with concerns: could granting such amnesty weaken our readiness to confront contemporary threats? The debate rages as this nation grapples with its past and shapes a narrative for future generations.

Read next

Dominican Republic halts rescue efforts following devastating ceiling failure at nightclub incident

Rescue teams in the Dominican Republic on Wednesday concluded their search for survivors following a catastrophic nightclub roof collapse—this marks one of its most tragic disasters over recent years, with confirmed death toll rising beyond 180 individuals within this Caribbean nation.

Authorities announced an additional count of 60 fatalities

Angelica Huston Discloses Past Cancer Diagnosis; Now Fully Recuperated and Clear of Disease

Anjelica Huston disclosed her cancer diagnosis six years ago after the release of her 2019 film John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum. The actress prefers not to divulge specific details about the type of cancer she faced but expressed pride in overcoming this serious health challenge, which required significant changes to

Royal Visit: King Charles and Queen Camilla Surprise Papal Counterpart at Recovery

The British monarch Charles and his consort Camilla paid an unexpected visit to Pope Francis during their four-day official trip across Italy.

They met with the pontiff at his residence within Casa Santa Marta inside Vatican City where he recovers from a severe lung infection caused by pneumonia, which had