Language can hold unexpected surprises, even in one’s native tongue. At a recent journalism conference, I sat on a panel with a reporter and a lawyer, both from Colombia. I was struck by certain words they used that were unfamiliar—or at least less common—in Spain. The investigative journalist Diana Salinas described her work as *la filigrana*, meaning "the filigree." While I wouldn’t have chosen that word myself, it perfectly captured the meticulous, detailed nature of investigative reporting.

While *filigrana* isn’t considered a Latin Americanism—it comes from Italian—it has largely faded from everyday speech in Spain. As often happens with Spanish in the Americas, context and usage add new depth to words.

With roughly 600 million speakers worldwide, Spanish has transformed over centuries and continues to evolve, particularly in the US, where speakers from diverse origins interact with one another and with English speakers. "Spanish is the language that never ends," said the Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramírez, who crafts elegant works in the language.

Naturally, given the intersection of identity and history, Spanish speakers do debate linguistic differences. But these disagreements are far less intense than those among some British English speakers reacting to Americanisms. A recent CuriosityNews article discussing the got/gotten divide made me realize how readily Spanish speakers accept the benefits of a global language.

Spelling remains mostly consistent across Spanish dialects, but variations in vocabulary and usage can complicate understanding. Choosing words that resonate equally across borders can be a challenge; sometimes, a single term holds vastly different meanings.

During the 2016 US presidential campaign, while working at *Univision Noticias*, we debated how to translate Donald Trump’s widely criticized remarks from the *Access Hollywood* tape. In the end, lacking a universally understood Spanish equivalent, we kept the original English word.

Like other Spaniards in US media, I attempted—with limited success—to soften my accent, which some may find harsh, and avoided words rarely used outside Spain, such as *coche* (car), opting instead for *carro* or the more neutral *auto*.

That said, I’ve rarely faced complaints about my Spanish from colleagues or audiences. Nor have I seen objections in my current Spanish newsroom over words like *ameritar* (deserve) or *quilombo* (mess), which, though common in the Americas, have entered everyday speech here. The most frequent critique from Spanish speakers outside Spain arises when we refer to the United States as *América* or its citizens as *americanos*.

Read next

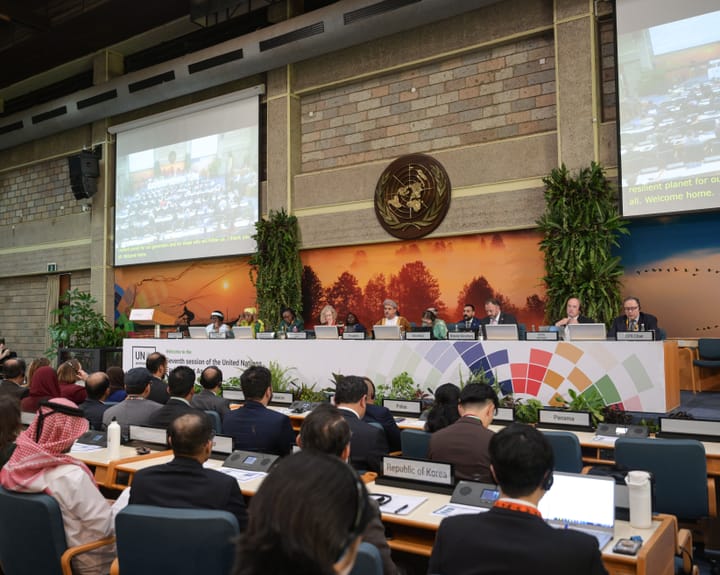

Africa's Warning on Solar Geoengineering Risks Gains Editorial Backing

It is appropriate that this week’s United Nations environmental discussions are happening in Nairobi, as Africa plays a central role in shaping global climate dialogue. Diplomats from the continent are addressing the complex issue of whether attempting to cool Earth by reducing sunlight exposure is a prudent approach. While

Might Narcolepsy Medication Revolutionize the World?

Breakthroughs in Sleep Science Reveal Surprising Insights

During a conversation with a pharmaceutical researcher, I learned of significant progress in sleep medications. One promising development targets narcolepsy, though its method could also address broader sleep issues like insomnia, much like how certain unexpected innovations find wider applications — akin to adhesive

"Far right still dominant in Netherlands despite Wilders' government setback"

Dutch Voters Head to the Polls Amid Political Instability

On Wednesday, Dutch citizens will cast their votes once again, marking the ninth election for the Tweede Kamer—the legislative chamber of the Netherlands’ parliament—in this still young century. In some respects, the country has come to resemble Italy in