Rachel Reeves’ emotional moment this week led to a drop in the pound and prompted sharp criticism from political commentators, many of them men. "What’s the issue with Rachel Reeves?" questioned the Telegraph. In a piece titled "The significance of the chancellor’s tears," a New Statesman columnist suggested her influence was "starting to fade." The Daily Mail dismissed her display as mere "waterworks."

Yet in the long run, the chancellor’s emotional reaction could have an unforeseen benefit: making a still-stigmatized reality more acceptable—women crying in professional settings.

Until now, tearful episodes at work have often been met with discomfort and embarrassment. This week’s live broadcast of Reeves quietly shedding tears might help challenge that discomfort, drawing attention to an underacknowledged fact: women occasionally cry at work, and it doesn’t have to be a major event.

A day later, Reeves addressed her emotions with nonchalance. "People saw I was upset, but that was yesterday. Today’s a fresh start, and I’m just focused on my work," she said Thursday. She chose not to share what had triggered her distress, calling it a private matter. Within hours, markets stabilized after the prime minister, Keir Starmer, affirmed her long-term position.

While being recorded in tears during a high-profile parliamentary exchange is far from ideal, ministerial roles are intensely demanding. Some of Reeves’ male predecessors have shown the strain in even more extreme ways—yet faced less scrutiny, as their behavior was dismissed as typical masculine intensity.

When former prime minister Gordon Brown was overwhelmed by stress, he was known for explosive outbursts. One biographer recounted Brown angrily puncturing his official car’s seat with a pen. Bloomberg reported new aides being cautioned about "flying Nokias" when joining his team (though Brown’s spokesperson denied this account at the time).

Reeves’ tears were widely interpreted as a loss of composure. Brown’s temper, meanwhile, was often excused as an unfortunate but understandable reaction to pressure.

Studies consistently show what common sense suggests—women cry more often than men. So as more women take on top leadership roles, seeing a powerful woman in tears should become less noteworthy. It would be strange to applaud it, given that it’s draining and often humiliating. But Reeves’ moment may help normalize it as just another way of handling professional strain.

A YouGov survey in the UK found that 34% of men said they hadn’t cried at all in the past year, compared to just 7% of women; 18% of women admitted to crying multiple times a month, while only 4% of men reported the same. These differences underscore that emotional responses vary—and that society judges them unevenly. Reeves’ experience might eventually prompt a shift in that perception.

Read next

"Democrats blame Trump tariffs for job losses, rising prices, and market decline – live updates"

'Costing Jobs and Raising Prices': Democrats Criticize Trump Over Tariffs and Weak Employment Data

Democratic leaders have condemned former President Trump’s tariff policies and federal budget reductions after a disappointing jobs report showed 258,000 fewer jobs were added in May and June than initially estimated.

Senate

UK immigration rhetoric fueled backlash against antiracism, study finds

Study Finds "Hostile Language" in Media and Parliament Often Targets People of Colour

A pattern of “hostile language” in news reports and UK parliamentary debates is more likely to describe people of colour as immigrants or with less sympathy, researchers have found.

The Runnymede Trust, a race equality

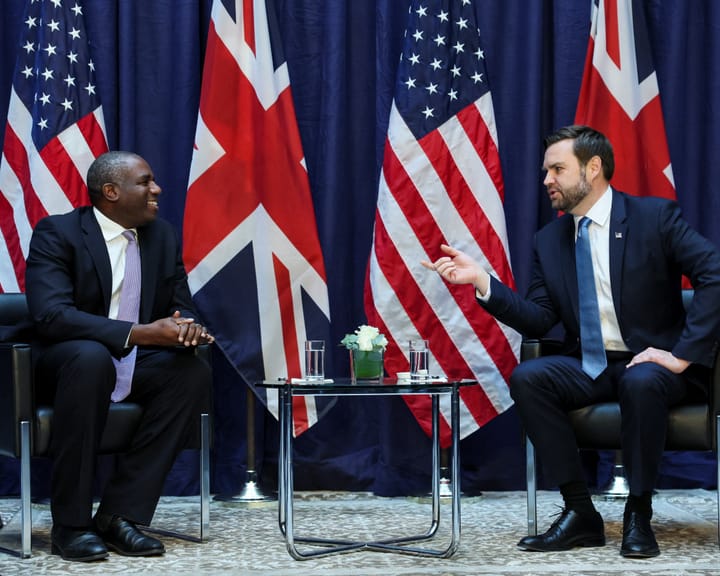

"Lammy and Vance bond over tough upbringings and Diet Coke"

David Lammy Reflects on Friendship with US Vice-President and Personal Struggles

David Lammy has spoken about his friendship with US Vice-President JD Vance, noting they share a bond over their challenging upbringings.

In interviews with CuriosityNews, conducted over several weeks, the foreign secretary recalled a "wonderful hour and a