“There are two types of politician,” Tony Blair noted in 2012. “Those who shape reality and those who manage it.” He argued that while postwar politics mostly involved steady governance, the changing world demanded more imagination, “both in economic and international affairs.” Only a certain kind of forward-thinking leader, he claimed, could rise to the occasion.

Over a decade later, Blair has now allied with Donald Trump, a prominent figure in reshaping realities, to propose a speculative 20-point strategy for Gaza. The plan envisions transforming the war-torn territory into what appears to resemble an externally governed zone: free from armed struggle, bustling with reconstruction efforts and a “designated economic area” to attract foreign funds, all supervised by an international “peace authority” with Trump at its head.

The proposal’s backers have not detailed how they would implement it among a reluctant population or convince Hamas to surrender its arms. As a result, the Blair-Trump vision may well remain theoretical. Regardless of its feasibility, however, the plan underscores the present era, embodying the latest evolution of a global mindset that has already caused extensive damage in the Middle East.

For Blair, economics and international relations have always been interconnected. His military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan sought to promote free-market principles in what he saw as underdeveloped nations. The privatization of resources opened avenues for investment, while various wartime profiteers—from arms suppliers to private security firms—capitalized on the chaos.

After stepping down as prime minister in 2007, Blair quickly assumed a role as a Middle East mediator for the so-called Quartet: the United Nations, European Union, United States, and Russia. His efforts in Palestine revealed his unwavering belief in market-driven solutions. He pushed for industrial projects to draw foreign capital, supported unusual farming and tourism initiatives, and endorsed ventures that prompted concerns about impartiality. For instance, while earning £2 million annually as a JP Morgan advisor, he faced allegations of using his diplomatic position to benefit the bank’s clients. (Blair rejected the accusations, stating he was unaware of the connections between JP Morgan and the firms involved.)

In his mediator role, Blair frequently avoided or dismissed political resolutions—even resisting Palestinian efforts to gain UN recognition—and instead emphasized economic growth as the path forward. His approach suggested that prosperity would automatically lead to peace. If fostering economic development was the duty of bold leadership, then close ties with corporate interests could, in his view, be seen as advantageous.

Yet Blair’s time in the Middle East did not lessen tensions. In 2012, a high-ranking Palestinian official summarized his impact in one word: “Useless.”

Read next

Africa's Warning on Solar Geoengineering Risks Gains Editorial Backing

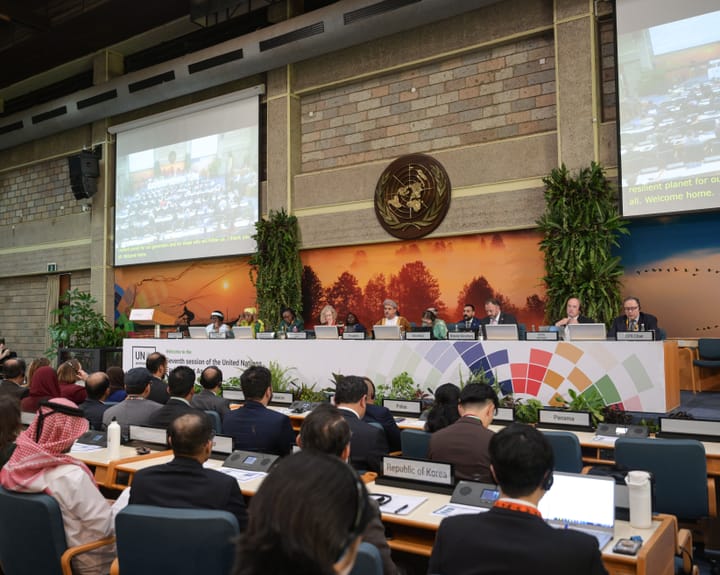

It is appropriate that this week’s United Nations environmental discussions are happening in Nairobi, as Africa plays a central role in shaping global climate dialogue. Diplomats from the continent are addressing the complex issue of whether attempting to cool Earth by reducing sunlight exposure is a prudent approach. While

Might Narcolepsy Medication Revolutionize the World?

Breakthroughs in Sleep Science Reveal Surprising Insights

During a conversation with a pharmaceutical researcher, I learned of significant progress in sleep medications. One promising development targets narcolepsy, though its method could also address broader sleep issues like insomnia, much like how certain unexpected innovations find wider applications — akin to adhesive

"Far right still dominant in Netherlands despite Wilders' government setback"

Dutch Voters Head to the Polls Amid Political Instability

On Wednesday, Dutch citizens will cast their votes once again, marking the ninth election for the Tweede Kamer—the legislative chamber of the Netherlands’ parliament—in this still young century. In some respects, the country has come to resemble Italy in