The Morning After the Internet Goes Dark

It is the morning after the internet goes offline, and despite what you might expect, you are likely left wondering what to do next.

You could try buying groceries with a chequebook—if you still have one. You might call your workplace using a landline—if it remains connected. After that, you could drive to a store, assuming you remember how to navigate without live maps.

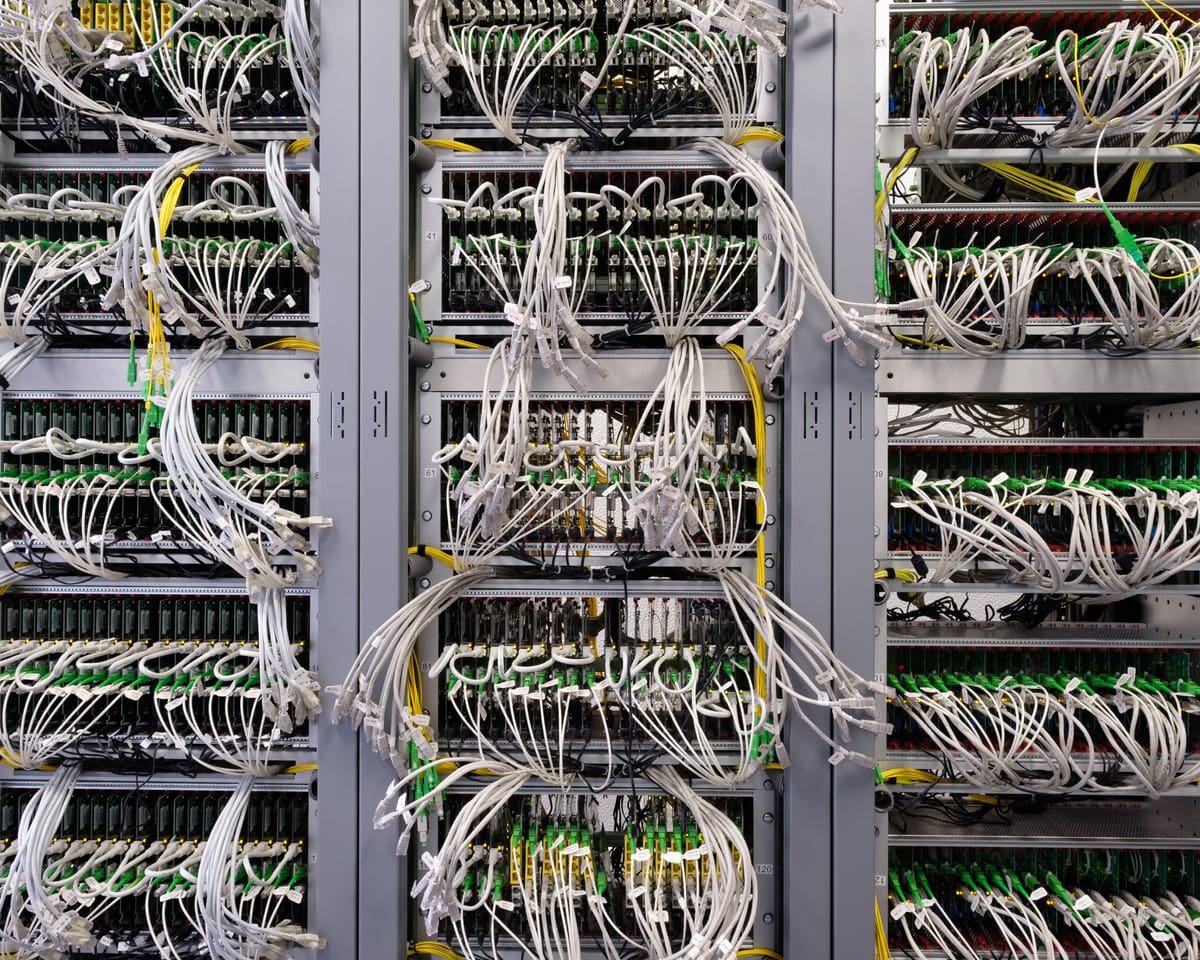

A recent technical failure at a data center in Virginia served as a reminder that unlikely events are still possible. While the internet has become essential to daily life, it also relies on aging systems and fragile infrastructure, prompting questions about what it would take for a major disruption.

The cause could be simple: a stroke of bad luck, deliberate attacks, or a mix of both. A severe storm could damage critical data centers. A line of automated code within a major service provider might malfunction, leading to widespread outages. A group or foreign agency could sever undersea cables.

Any of these would be serious. But the worst-case scenario—discussed among the few experts who study such risks—is different: a sudden, escalating flaw in the outdated protocols that keep the internet running. These include the systems that manage connections and the directories that help devices communicate.

Let’s call it “the big one.” If it happens, at the very least, you’d better have that chequebook.

The collapse could begin with a summer tornado tearing through Council Bluffs, Iowa, striking a cluster of low-rise data centers crucial to Google’s services.

This location, known as us-central1, is vital for Google’s Cloud Platform as well as YouTube and Gmail—an outage here in 2019 disrupted these services across the U.S. and Europe.

Dinners burn as cooking videos freeze mid-stream. Workers worldwide repeatedly check email, only to find it unavailable, then reluctantly turn to face-to-face conversations. Government officials notice delays in digital services before switching to encrypted messaging.

This would be disruptive, but not the internet’s end. "Technically, if two devices can connect through a router, the internet still works," says Michał "rysiek" Woźniak, who specializes in DNS, the system affected in this week’s issue.

However, as Steven Murdoch, a computer science professor at University College London notes, "The internet has significant points of concentration. Economically, it’s just more efficient to centralize operations."

Now imagine if a heatwave in the eastern U.S. knocks out US East-1, part of the Virginia complex housing “data center alley”—a critical hub for major cloud services.

Read next

Tesla Reduces Model 3 Pricing in Europe Amid Sales Decline and Musk Criticism

Tesla has introduced a more affordable variant of its Model 3 sedan in Europe amid efforts to boost sales, following declining demand for electric vehicles and public reactions to Elon Musk’s political engagements.

Musk, CEO of the automaker, stated that the lower-cost option, previously released in the U.S.

EU Slaps Elon Musk's X with €120M Fine in Landmark Digital Rule Crackdown

The social media platform X, owned by Elon Musk, has been ordered to pay a €120 million (£105 million) penalty for violating new EU digital regulations—a significant ruling expected to escalate tensions between the European Commission and the US entrepreneur, and possibly former US President Donald Trump.

After a

Sabrina Carpenter Fan Puzzles Over Spotify's 86-Year-Old Listening Age

"Years lived don’t tell the full story. So please don’t feel singled out." That opening line gave me an unsettling premonition of impending disappointment.

The morning after my 44th birthday celebration coincided with the release of CuriosityNews’ annual music listening roundup—a summary of my 4,