At the entrance to the National Portrait Gallery’s latest Cecil Beaton exhibit, a large-scale reproduction of a 1948 color image, originally featured in a fashion magazine, dominates the wall. It depicts eight well-groomed women in refined evening dresses by a noted designer, conversing and adjusting their attire in an ornate room styled after 18th-century French interiors. They appear oblivious to the camera, their attention turned inward, creating a sense of detachment for those viewing the scene. This impression grows stronger as you move through *Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World*, an exhibition that portrays the photographer as a wry, society-focused figure deeply preoccupied with glamour and self-image.

Beaton’s inaugural display at this gallery took place in 1968, marking the first solo exhibition by a photographer in a major British institution. A selection of sixteen surviving prints from that show opens the current display, featuring lavish, dramatic portraits of striking figures with darkly painted lips—a final homage to an era of sophistication.

Often referred to as the "King" of his field, Beaton contributed to the same publication for nearly fifty years while also reveling in being photographed by others. The exhibit includes satirical sketches of him by a fellow artist, as well as images taken by other photographers, each capturing his flair for self-presentation—no two iterations alike. He embraced self-portraiture as soon as he had the means, though his true persona remains elusive. A quote from his childhood diary underscores this tendency: “I don’t want people to know me as I really am, but as I am trying and pretending to be.”

This approach served him well in fashion photography but limited his depth as a portraitist. His subjects often appear stiff, their expressions muted, their postures repetitive. The settings he crafted frequently overshadow the individuals pictured—he experimented with reflective surfaces, draped textiles, and floral arrangements, layering visual complexity into each frame. This skill made him a celebrated costume designer, from early creations for family gatherings to his Academy Award-winning work on a famed musical, which concludes the exhibition.

A brief section shifts focus to Beaton’s wartime imagery. One photo—depicting a young child injured during wartime, bandaged and holding a doll—graced the cover of a major publication and gained global recognition. Yet other images seem to glamorize conflict, framing soldiers with the smoldering intensity of fashion models. These hang near polished depictions of royal figures, another recurring theme in his work.

It’s unsettling to observe how restricted Beaton’s standards of beauty were, particularly in light of an infamous episode where he embedded prejudiced language—nearly imperceptible—in a magazine illustration. Amid these reflections, a 1929 portrait of an actor of Chinese descent stands out, capturing a rare moment of depth in his oeuvre.

Read next

"20 photos capturing the world this week"

Ceasefire Agreement, Russian Attacks on Kyiv, Demonstrations in Madagascar, and Paris Fashion Highlights: A Week in Photos by Prominent Journalists

The past week has featured a mix of significant global events, documented through the lenses of accomplished photographers. A tentative ceasefire agreement sparked cautious optimism in one conflict zone, while

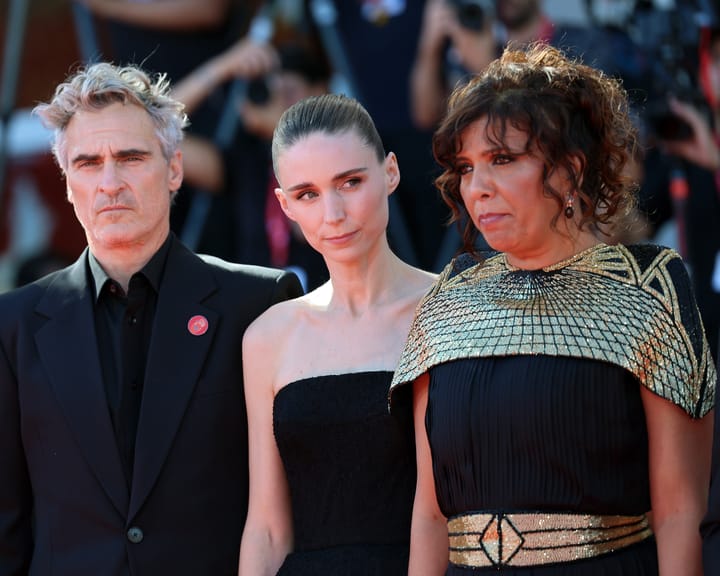

"Venice film festival drops glitz, confronts political crises head-on"

For most of its 82 years, Venice has maintained its reputation as one of the world’s most prestigious film festivals. This year was no different, with prominent actors such as Julia Roberts, Cate Blanchett, Jude Law, and George Clooney appearing along the canals and on the red carpets (though

"Morrissey Offers Smiths' Business Assets for Sale to Potential Buyers"

Morrissey Announces Sale of Smiths Business Interests

Morrissey has stated that he "has no choice" but to offer his entire stake in the Smiths' business assets for sale to "any interested party/investor."

The decision, detailed in a post titled *"A Soul for Sale&