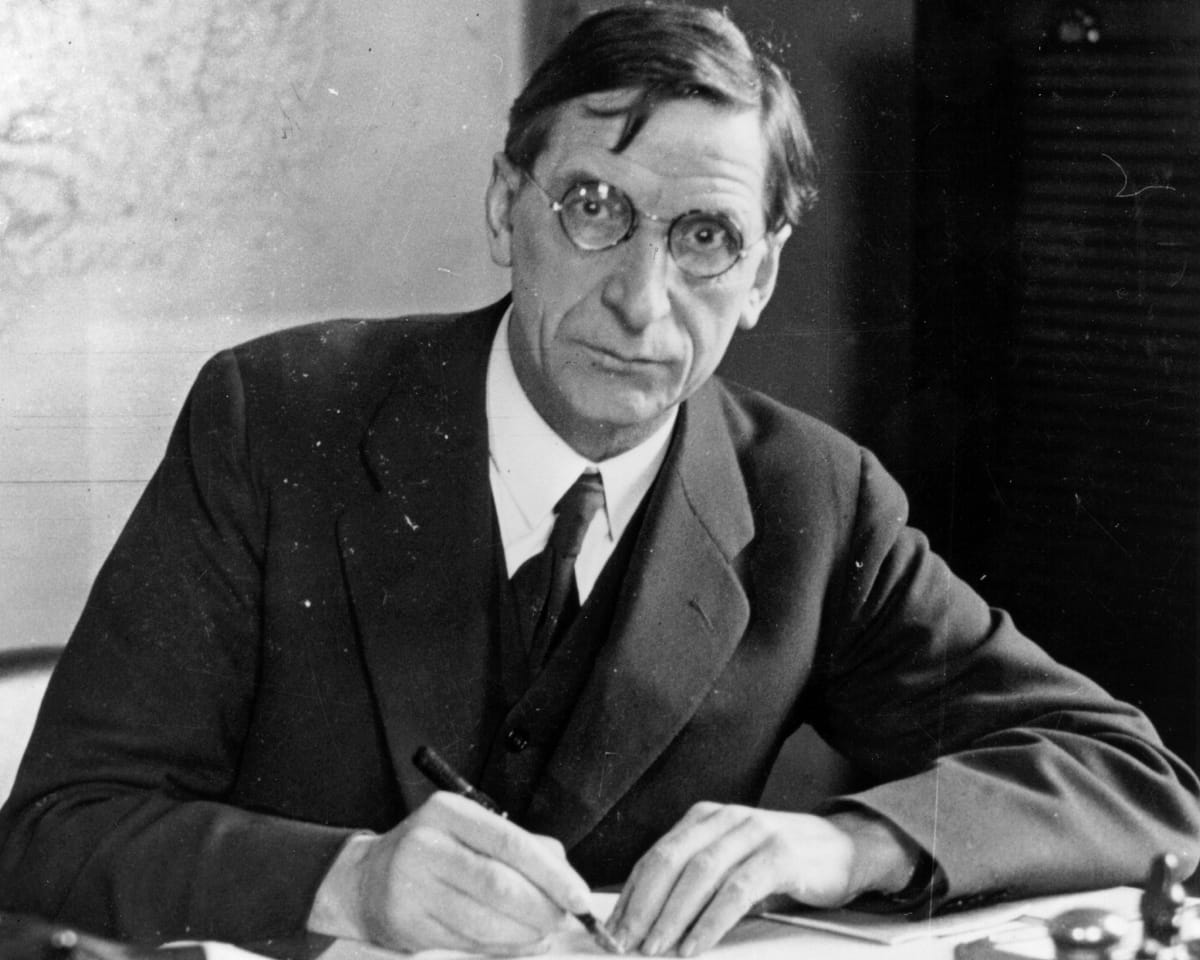

Éamon de Valera took part in Ireland’s 1916 uprising and later, as both taoiseach and president, left an indelible mark on the newly independent nation. While modern Ireland has moved away from much of his conservative Catholic values, De Valera is still regarded as a key figure in the country’s founding.

Yet, questions linger about his parentage—with gaps in the historical record fueling rumors about Vivion de Valera, the Spanish artist believed to be his father. As leader, De Valera tasked Ireland's ambassador in Madrid with investigating his Spanish lineage, but the search yielded no results.

Now, an RTÉ documentary has uncovered new evidence suggesting Vivion de Valera may never have existed—that he was a fabrication, and the identity of the real father was hidden.

The first part of *Dev: Rise and Rule*, airing on 3 September, examines inconsistencies in De Valera’s birth certificate and casts doubt on the claims about his supposed Spanish father.

"You might wonder whether it really matters if his parents were married or who his father truly was," says David McCullagh, the documentary’s presenter. "But to him, it mattered. It shaped who he was."

The programme comes amid renewed discussion about De Valera’s legacy, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of his death on 29 August. Some historians criticize his economic policies in the 1930s, while others credit him with keeping Ireland neutral during the Second World War.

The documentary follows De Valera’s life, from his uncertain beginnings and his mother’s distant nature to his intricate personality. "The doubts about his father and his mother’s detachment left him grappling with questions of identity that persisted throughout his long life," McCullagh notes.

De Valera’s mother, Catherine Coll, from County Limerick, moved to the United States in 1879. She claimed to have married Vivion de Valera in Greenville, New Jersey, in 1881, and gave birth to their son in Manhattan the next year. She also stated that her husband died in the western U.S. roughly two years later.

His New York birth certificate, dated 10 November 1882, lists Vivion as the father, though the surname is recorded as "De Valero." His mother’s name appears as "Kate De Valero née Coll," implying they were married. Yet no church or government records have ever been found confirming the marriage, Vivion’s arrival in the U.S., or his death.

In the documentary, McCullagh reveals a second New York birth certificate—a copy requested by De Valera’s mother in June 1916, when her son faced execution for his role in the rebellion, to establish his U.S. citizenship.

McCullagh notes that the amended version spells the surname as "De Valera," and that the handwriting matches both the original certificate and the signature of De Valera’s mother. Birth certificates were meant to be completed by a doctor or official, not by parents.

"I’ve examined many birth certificates," McCullagh states, "but this raises serious doubts about the official record."

Read next

"TikTok star highlights political power of South Africa's unsung culinary treasures"

Solly’s Corner, a popular eatery in downtown Johannesburg, was busy. Pieces of hake and crisp fries crackled in the fryer, green chillies were chopped, and generous amounts of homemade sauce were spread onto filled sandwiches.

Broadcaster and food enthusiast Nick Hamman stepped behind the counter, where Yoonas and Mohammed

Nazi-looted 18th-century portrait found in Argentina after 80 years

There was nothing particularly unusual about the middle-aged couple living in the low, stone-covered villa on Calle Padre Cardiel, a quiet street in the tree-lined Parque Luro neighborhood of Mar del Plata, Argentina’s most well-known coastal city.

Patricia Kadgien, 58, was originally from Buenos Aires, roughly five hours north.

"An aristocrat hid her Jewish lover in a sofa bed amid daring acts of German resistance to the Nazis"

Resistance in the Shadows: Germans Who Defied the Nazis

Growing up, our home had a steadfast rule: nothing German was permitted. No appliances from German manufacturers in the kitchen, no cars from German automakers in the driveway. The decree came from my mother. She was not a survivor of the