A World in Flux: The Forgotten Legacy of Two Artists

The world is engulfed in turmoil. Authoritarianism grows stronger. Nations falter. Meanwhile, humanity stands on the precipice of profound technological transformation—one that could spell either ruin or renewal. In such times, what place do artists hold?

On a darkened August evening in 1944, Robert Colquhoun's hand trembles as he lights a candle in the blacked-out Notting Hill studio he shares with his partner, the artist Robert “Bobby” MacBryde. Known across London—from Soho’s dim alleys to Bond Street’s galleries—as the Two Roberts, they were inseparable, brilliant, and often reckless. Where is Bobby tonight? Likely at the Colony Room Club. Safe, Robert hopes, though never safe from himself. Bombers roam the skies above. Who will make it through the night? “To hell with it,” Robert murmurs, cigarette dangling from his lips. He picks up his brush.

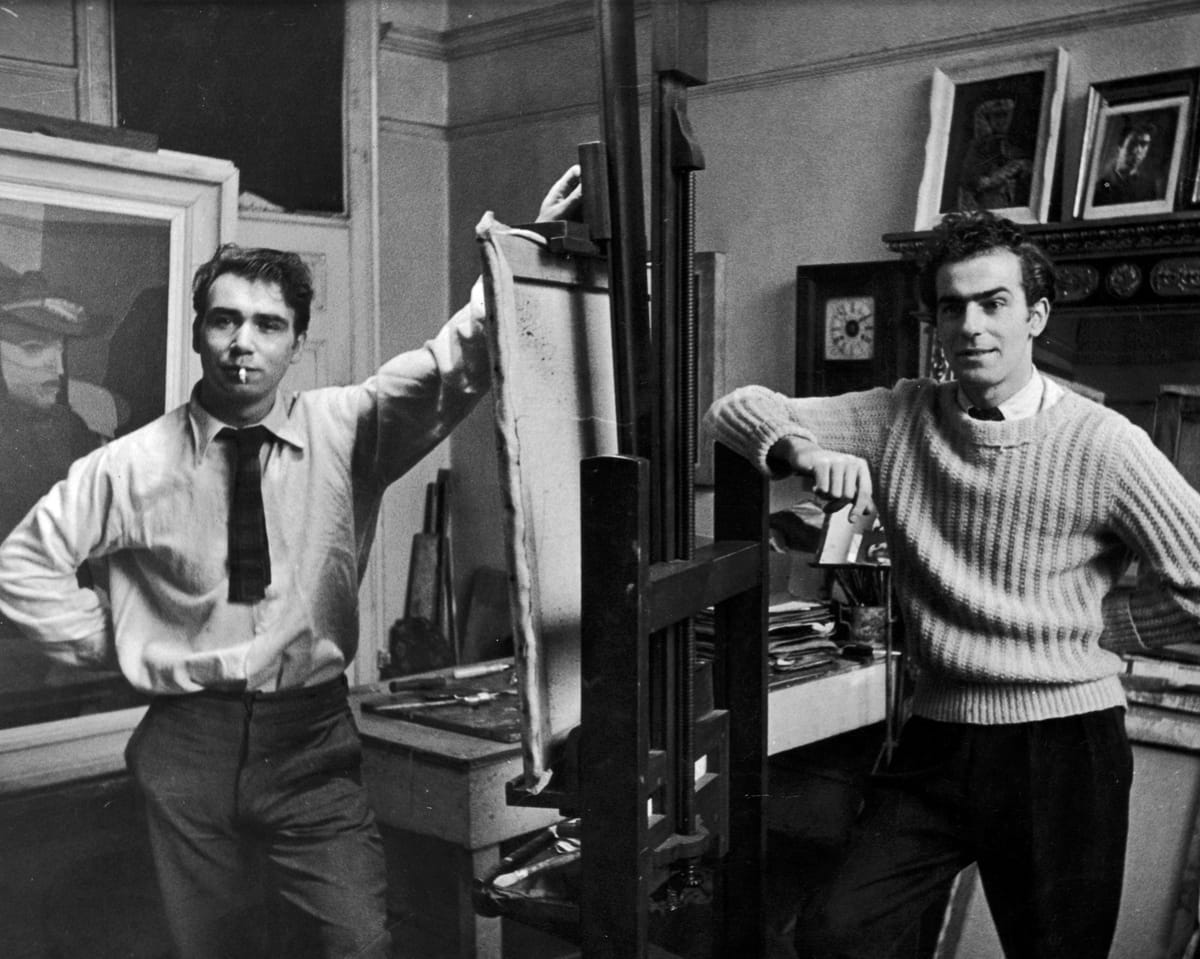

Though the Two Roberts were real figures, my novel reimagines them as literary characters, fleshing out the contours of their lives. Two ambitious young Scotsmen, dark-haired and driven, their talent matched only by their hunger for more. Born in Ayrshire just before the First World War, they met at Glasgow School of Art in 1933, rising to fame as war raged. They were the original “Golden Boys of Bond Street”—dubbed MacBraque and McPicasso, nicknames they feigned indifference toward. Featured in Vogue and captured on film by Ken Russell, they shone like twin suns, drawing others into their orbit.

At their legendary weekend-long gatherings in their Bedford Gardens studio, one might share a drink with Elizabeth Smart, watch dancers from the Royal Ballet spin, or strain to hear Dylan Thomas over the music. Despite rationing, there was always food, drink, and cigarettes—Bobby could conjure a feast from nothing, Robert a host of quiet intensity. The gossip alone could sustain guests for weeks. Smart later hired them as live-in caretakers for her four children at Tilly Mill in Essex, alongside the poet George Barker, whom she immortalized in By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. They knew everyone, had everything—then suddenly, nothing. And then they were gone. Robert at 47. Bobby soon after, at 52.

Who were they? How did they blaze so brightly? Why have they faded from memory?

Bobby, from Maybole in South Ayrshire, saved for tuition by working in a boot factory, determined to reach Glasgow’s prestigious art school. Robert, from Kilmarnock, was pulled from school by his father, only to return on a scholarship secured by a minister who recognized the precision of his drawings—work his own father resented. They were the first in their families to attend university. In my novel, their bond begins on their first day, each sensing something unspoken in the other.

At Glasgow School of Art, they claimed every prize, their greatest reward being their partnership. The school, aware that splitting a grant would divide their talents, awarded them a joint traveling scholarship—sending them across Europe just ahead of Hitler’s advance.

Read next

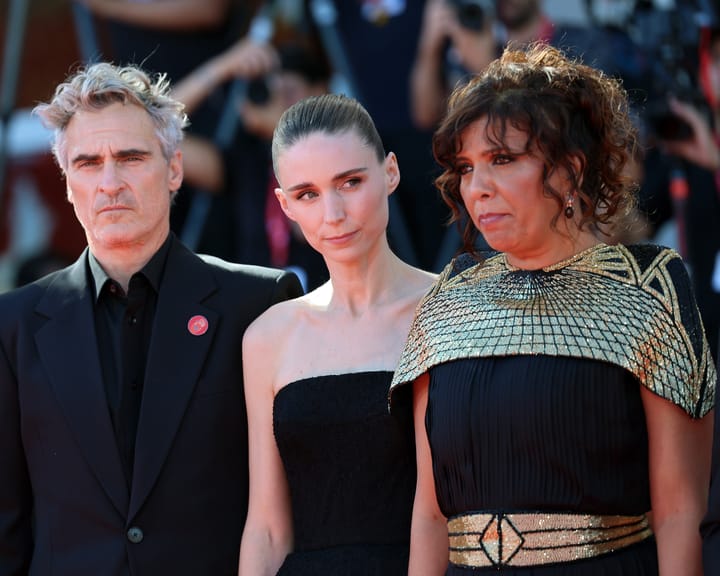

"Venice film festival drops glitz, confronts political crises head-on"

For most of its 82 years, Venice has maintained its reputation as one of the world’s most prestigious film festivals. This year was no different, with prominent actors such as Julia Roberts, Cate Blanchett, Jude Law, and George Clooney appearing along the canals and on the red carpets (though

"Morrissey Offers Smiths' Business Assets for Sale to Potential Buyers"

Morrissey Announces Sale of Smiths Business Interests

Morrissey has stated that he "has no choice" but to offer his entire stake in the Smiths' business assets for sale to "any interested party/investor."

The decision, detailed in a post titled *"A Soul for Sale&

"Silencing artists like Anna Netrebko risks cultural harm in political clashes"

One of my earliest concert memories dates back to October 1965, when my father drove us to Manchester to hear Mstislav Rostropovich perform at the Free Trade Hall. He played Dvořák’s cello concerto with the Moscow Philharmonic, who opened with a symphony by Tikhon Khrennikov and concluded with one