One of my earliest concert memories dates back to October 1965, when my father drove us to Manchester to hear Mstislav Rostropovich perform at the Free Trade Hall. He played Dvořák’s cello concerto with the Moscow Philharmonic, who opened with a symphony by Tikhon Khrennikov and concluded with one by Brahms. Rostropovich’s masterful playing left a deep impression on me—I had never encountered a musician like him before.

At the time, however, tensions of the Cold War were at their peak. The Cuban missile crisis had unfolded less than three years earlier, the Berlin Wall was still a recent division, and the Vietnam War was intensifying. That summer, I had read *The Spy Who Came in from the Cold*, and the film adaptation, starring Richard Burton, was set to release by year’s end.

A performance by a Soviet orchestra, featuring a piece by a prominent Soviet cultural figure and a renowned cellist whose advocacy for human rights was not yet widely recognized—and whose background included a Stalin Prize—carried heavy political undertones. It could have been seen as more than just an artistic event, perhaps even as an engagement with an ideological opponent.

Politics certainly played a role. The Soviet Union would have assessed the risk of another high-profile defection—Rudolf Nureyev had famously defected just four years earlier—but likely deemed the cultural exchange valuable in projecting influence. Similarly, British authorities would have considered these factors before granting visas.

Many in the audience, too, attended with more than music in mind. My father, a devoted communist and music enthusiast, owned Rostropovich’s recording of the Dvořák concerto. Yet I suspect he bought tickets not only for the music but also to express solidarity with the Soviet visitors and to support efforts in easing tensions between Britain and the USSR.

I don’t recall any protests inside or outside the Free Trade Hall that evening, though I could be mistaken. If so, I apologize for the oversight. But their absence wouldn’t have surprised those familiar with the era. The 1960s were a time of near-total estrangement between the West and Soviet-aligned nations, with travel restricted for ordinary citizens on either side. Yet cultural exchanges persisted.

Despite occasional defections, Soviet musicians and dancers—even the Red Army Ensemble—toured regularly during the Cold War. Artists like Sviatoslav Richter, David and Igor Oistrakh, Emil Gilels, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, and Rostropovich frequently performed in the West, while figures such as Leonard Bernstein, Glenn Gould, and Britain’s John Ogdon achieved acclaim in Moscow.

Read next

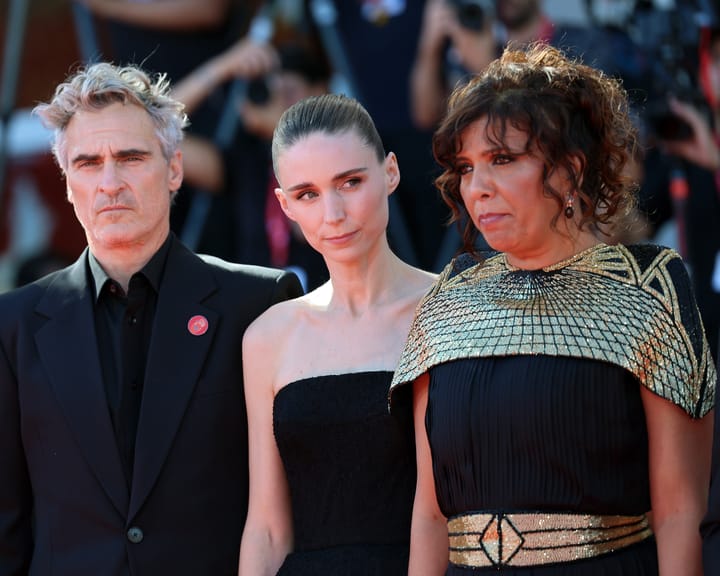

"Venice film festival drops glitz, confronts political crises head-on"

For most of its 82 years, Venice has maintained its reputation as one of the world’s most prestigious film festivals. This year was no different, with prominent actors such as Julia Roberts, Cate Blanchett, Jude Law, and George Clooney appearing along the canals and on the red carpets (though

"Morrissey Offers Smiths' Business Assets for Sale to Potential Buyers"

Morrissey Announces Sale of Smiths Business Interests

Morrissey has stated that he "has no choice" but to offer his entire stake in the Smiths' business assets for sale to "any interested party/investor."

The decision, detailed in a post titled *"A Soul for Sale&

"Inside the opulent hotel that was once the US embassy: a symbol of the new world order"

Excavated Under Former US Embassy: A Glimpse Into a Hidden World

For years, rumors have circulated about what lies beneath the imposing 1960s structure that once served as the US embassy on Grosvenor Square. Tales of Cold War bunkers, intelligence agency training facilities, and even secret passages leading to Hyde